Foreword: Last year in November I wrote a follow-up article, from one I wrote 19 years earlier, on 五本組手 (Gohon Kumite). In that piece, I mentioned that I'd write a 'secondary follow up article', so here it is. Rather, than moving on to other forms of kumite, I thought I'd recap some key points featured in the previous article and answer a number of questions I've received since then on this topic; moreover, expand on these aspects. Overall, I hope that you find this article useful. As always I look forward to hearing your feedback and questions, All the best in your training and greetings from my dojo here in Oita City, Japan, Osu, André

Generic description of Gohon Kumite and format of this article:

Here is a brief description of the ‘basic’ form of Gohon

Kumite (Five step ‘sparring’. This form

of engagement match is the required ‘Kumite’ for the Hachiryu and Nanakyu

examinations. In this article I will: (a) describe basic Gohon Kumite; (b)

provide some ‘additional key points for ‘Basic’ Gohon Kumite’; (c) explain more

advanced Gohon Kumite and list some variations; and (d) wrap up with some

conclusive notes. Overall, while I written about this topic before, I hope that

this latest article provides yet another analytical lens on Gohon Kumite as a

Shotokan Karate training routine.

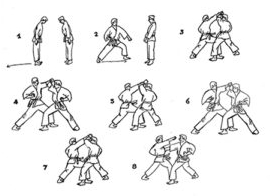

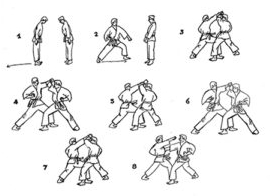

Both attacker and defender are decided. After ojigi (bowing)

they face each other in hachiji dachi: ryo ken daitai mae. Being at the correct

distance to make maximum impact, the designated attacker steps back with the

right foot to execute gedan barai in hidari zenkutsu dachi. It is probably

worth mentioning that some instructors and groups kiai when making this ready

position, however, I do not.

The attacker then announces ‘joudan’ then precedes to attack

five times with alternate seiken jodan oi zuki and a sharp hikite each time to

aid in this process. Each time the opponents jinchu (the upper lip, just below

the nose) is targeted, and the aim is to use zenkutsu dachi to attack without

breaking the shomen position of the hips. In this process the drive and stretch

of the sasae ashi is paramount. Attack with the kahanshin. On the fifth and

final tsuki kiai strongly

To fend off these five tsuki the defender retreats five times in zenkutsu dachi receiving each attack with jodan age uke over their lead leg.

In contrast to the opponent driving forward into shomen, the defender strongly

rotates the hips into hanmi to launch their uke. Again, the hikite is fully

applied to increase the velocity and power of each ukewaza. The essential point

of stepping rearward is that the rear leg is slightly bent for both balance and

reciprocal action. When turning into hanmi this also allows the hips to remain

anatomically level. On the fifth step the defender straightens the rear leg to

apply ground power to rotate the hips for a strong counterattack with a gyaku

zuki. This counter is either aimed at the opponents jinchu or the suigetsu

(solar plexus).

From here both the attacker and defender return to hachiji

dachi with ryo ken daitai mae. The attacker steps back whilst the defender

steps forward. The roles of attacker and defender are then reversed, and

process repeated.

After both sides have attacked and defended against ‘jodan’,

chuudan (seiken chudan oi zuki) is then practiced. The process is the same

however the ukewaza employee is chudan soto uke.*

* Note — for middle kyu ranks and up, the hangeki

(counterattack) is always distance and angle appropriate. For example, when too far away a mae geri or another kick may need to be utilized. Likewise, when too

close, an enpi may be optimal. In sum an incorrectly distanced gyaku-zuki,

unable to break a solid board is indicative of its incorrect deployment.

How about ‘mae-geri’?

In the eighties we also practiced attacks with chudan

mae-geri keage in standard ‘Basic’ Gohon Kumite (including the 8th and 7th Kyu

examinations). However, this is generally not included now (as lower grades

tend to get bruised up pretty badly, sometimes worse). Of course, the great

thing about attacking and defending against mae-geri in Gohon Kumite is that

one “…learns to do gedan-barai correctly” and also a proper trajectory with

your front snap kicks. I have many memories of egg shaped purple bruises on the

insides of my shins and forearms. It also wasn’t uncommon for lower grades to

be downed: via a solid kick to their solar plexus. A quick way to learn that

‘zenkutsu-dachi is used to escape’ and one’s uke is in fact the secondary waza;

that is, ‘the back up technique’/‘the cover’. Taken as a whole, I probably

don’t think that mae-geri in Gohon Kumite—for beginners here now, in 2022—is

probably a good idea. Nonetheless, it is excellent training for senior kyu

grades and above: once ‘technique and conditioning’ is sufficient..

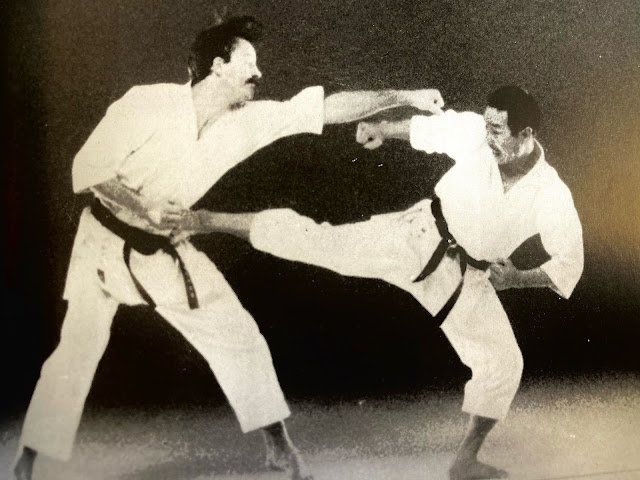

At one Dan Examination, when I was sitting next to Asai

Sensei, he leaned over to me and quietly said “Gohon Kumite”. All of the Shodan

candidates had just completed the Jiyu Ippon Kumite portion of the test. So, I

informed the candidates and had them form staggered lines, adjacent to our

table.

Asai Sensei then stood up and announced “attack ‘mae-geri, defend gedan-barai, no count”.

It was immediately clear that all of the candidates could not

manage deflecting the mae-keriwaza coming in at them. They messily attempted

zig zagging maneuvers to escape from the line. Likewise, it was clear that they

were getting hurt when kicking and, after the second kick, were purposefully

missing to avoid bruising to their shins. Overall, what was relatively clean

and sharp jiyu ippon was erased by the inability to do the most basic Shotokan

kick and (gedan barai) which, of course, is one of the five core ukewaza. Taken as a whole, it was a disaster,

resulting in all of the Shodan candidates, failing the examination.

So what’s the lesson to be learned here? If you can’t

deflect a full speed, full power mae-geri front on (without taisabaki) with

gedan-barai, your gedan-barai is wrong. Furthermore, if you can’t deflect five

consecutive full speed, full power mae-geri (plural) going rearward on the line

(with gedan-barai), your gedan-barai is not reliable. Lastly, if don’t hit your

training partner in the solar plexus five times—if they don’t make a good

gedan-barai—your mae-geri keage is incorrect.

To conclude, if you think you ‘need to get hurt and just be

tough’ to properly defend against mae-geri in Gohon Kumite, you are also wrong.

Correct ‘timing and distance of the rearward’ step into zenkutsu dachi, koshi

no kaiten, shime of the wakibara, hikite, and correct timing of the forearm

twist will result in you deflecting the biggest and fastest of

opponents/training partners. In saying that, when committing with any chudan

kicks, there is the inherent risk of bruising. But this is something one gradually

gets used to. That being said, with a good linear trajectory, bruising will be mitigated. The key here is that when you plant your kick you do so with strict

form and utter commitment.

Some additional key points for ‘Basic’ Gohon Kumite:

a. With age

uke and soto uke utilize the wrist; furthermore, target your opponents wrists

(for mae-geri and other kicks target the ankle).

b. Beware of

trajectories when making all tsuki and ukewaza. Tsuki must be as direct as

possible and uke must use the proper arcs and connect to the wakibara. Avoid

over-stretching tsuki and, indeed, ‘over blocking’ with uke.

c. When

attacking and defending move in a straight line. This is for effective

attacking and training your defense under maximum pressure.

d. Use your

stance when attacking to overwhelm the defender; likewise, when defending, use

your stance to escape. This form of ‘kumite’ highlights it’s better to be out

of distance than to rely solely on ukewaza. This is a key lesson of Gohon

Kumite.

e. When

attacking collapse the front knee and utilize juryoku (gravity) without

breaking the posture; furthermore, the fist should impact slightly before the

stance is completed. The purpose of this is twofold, firstly, hand speed is

increased, and secondly, the movement of the center and optimal mass can be

transferred into the target.

f. After

your final attack do not try to physically escape from your opponents

counterattack. Instead, allow them to counter you. I know of people who have

tried to avoid being countered and, here in Japan, (if you are with a senpai) it will sometimes erupts into Jiyu Kumite. The key here is to watch the

hangekiwaza, and visualize countering of their respective counterattack. This

skill of visual analysis is very valuable even in the context of basic Yakusoku

Kumite.

g. When

attacking, always aim to hit. Contact depends on the training partner

(comparative size, strength, health, experience, etc...) and what’s agreed on

beforehand. Common sense and mutual respect is the key here. Even if there is

no contact, even with young children, still aim for maximum speed and power,

distancing and targeting, but don’t touch. In this way, even without contact,

training time is not wasted for both partners.

h. When

countering, counter with full speed and power but make no contact. Your

training partner is trusting your control and giving their body to be your

target. Respect them!

i. Try to

match your kokyu (breathing) with the attacker. From the eyes to the shoulders

form a triangle for observation. You should see all four limbs, also

maintaining peripheral vision. Practice to be aware of all your surroundings,

this simple drill allows one to practice such skills, which can be further

developed in higher level training routines.

More advanced Gohon Kumite:

What I’ve covered up until now is the basic ‘grading form’

of Gohon Kumite. For higher practitioners, there are many variations. In

particular, higher grades practice with greater intensity when attacking. Also,

the counterattacks used must be optimal based on distancing and target

availability. The counterattack employed must be instantaneously selected and

optimal for that moment. The capacity to cause maximum damage in that moment is

what dictates this reactive hangeki (counterattack).

Here are some variations of Gohon Kumite:

1. Continuous

fast attacks and defense: tobi konde five times etc..

2. Broken

kankyu (rhythm)/timing.

3. Uke and

hangeki on every step.

4. Only

using the techniques from one particular kata or group of kata.

5. Utilizing

different attacks, heights of attacks, ukewaza, tachikata, unsoku etcetera.

6. Attacking

with a renzokuwaza on each step.

7. Moving in

different directions with attacks and/or defenses.

8. Tenshin.

9. Combinations

of the above…

As you can see, the possibilities are virtually unlimited.

In saying that, as I often stress, ‘innovation for the sake of innovation is

time not well spent’. Accordingly, when a variation is used, the achievement

objectives should be well defined and concentrated. Moreover, this should be

steered by the overarching objective of developing/enhancing budo/bujutsu

karate skill.

The use of 三本組手

(Sanbon Kumite):

You will know that some dojo and groups utilize Sanbon

Kumite as opposed or in addition to Gohon Kumite. Sanbon Kumite is sometimes

used when there is simply less space; however, some groups, such as SKIF

(Shotokan Karatedo International Federation) treat it as a different form of

kumite and use it to practice different level/height techniques on each step;

namely, jodan, chudan then mae geri. Asai Sensei, and JKA style Shotokan karate

as a whole, treat Sanbon Kumite in such a manner, as “…not a separate form of

training but, rather, a variation of Gohon Kumite”. I am by no means saying

that one way is better than the other; rather, I’m merely pointing out this

difference in approaches.

Conclusive notes:

Sometimes to wrap up a class I might use an innovative form

of yakusoku kumite, such as those listed above. In that case, it might just be

a hard out conclusion of the session (to sweat and train spirit). That being

said, when serious practice of Gohon Kumite is the aim, I teach and practice it

primarily as a form of ‘partner kihon’. That is, when fighting is my aim, I

prefer to do jiyu kumite, impact training etc. Certainly, I’m not completely

diminishing variations here; however, I am putting them in their rightful place

(from the overarching budo/bujutsu karate perspective).

© André Bertel. Oita City, Japan (2022).