© André Bertel. Oita City, Japan (2021).

This is one of the initial basic stationary drills for the practice of open handed uchiwaza. In this case, shuto sotomawashi uchi, shuto uchimawashi uchi, shuto tateotoshi uchi and haito sotomawashi uchi.

This site is based on my daily practice of Shotokan Karate-Do here in Oita City, Japan. More than anything else, unlike the majority of other karate websites, this page is primarily dedicated to Budo Karate training itself; that is, Karate-Do as a vehicle for holistic development.

© André Bertel. Oita City, Japan (2021).

This is one of the initial basic stationary drills for the practice of open handed uchiwaza. In this case, shuto sotomawashi uchi, shuto uchimawashi uchi, shuto tateotoshi uchi and haito sotomawashi uchi.

Today I’d like to use two major joints/regions of the body to elucidate the essential ‘advanced variations’ in karate as bujutsu. Today, a brief case study of the hips and shoulders. Of course, the hips and shoulders are the base joints for all four respective limbs, so their utilization—technically and level of control and flexibility—is of paramount importance.

|

| Classical training underpins freestyle but cannot effectively work without it. |

In saying that, I’d like to shift away from

the technical execution and turn to their use in actual fighting, at least at an entry point.

Obviously, pure kihon (the 'standard foundational techniques') is the baseline for

everything else. Nevertheless, while this is always a major aspect of practice,

to reach a high level in karate 'as bujutsu' (that is, karate as an optimal unarmed combat system), one cannot train only at this

baseline. Irrespective of “...how good one becomes at the ‘standard kihon’ (also kata, and 'karate centric kumite'), this

alone will not fully translate into effective techniques in the real world”.

Rather, from the reference point of the

base kihon, “...one must spontaneously deviate accordingly, in response to any

given circumstance of violence, and do so in relation to one’s own unique

attributes”.

Now, returning specifically to today's topic: the hips and shoulders...

Firstly, let me begin with koshi (the

hips). It’s important for people who don’t speak Japanese to understand that

Japanese mean your back and butt when they mean ‘the hips’; also, ‘the waist.

Often I find westerners get fixated on the kokansetsu (the hip joints). Instead

of doing this, to properly ‘use your hips’ you must focus on using the entire

aforementioned region which, of course ‘includes the kokansetsu’.

Of course you can rotate the hips into

various degrees of hanmi and gyaku-hanmi, from these positions to and from

shomen, simultaneously thrust the hips forward or do so independently, drop the

hips, raise the hips, and tilt them.

These are all ‘standard’... Moreover, they

all vertical and, occasionally, straight line horizontal postures.

In actual fighting, outside of karate

matches, this upright posture is often dangerous. That is why, breaking the

posture of the hips in defense and for more spring in offensive techniques is

an important skill. The most obvious example of this is Asai Sensei’s posture,

which he was and still is, often criticized for. That is, he allowed his koshi

to relax rearward to slightly fold his body. In actual fact, this position

allows much more cover, is far more mobile, and as said before—allows greater

thrust/spring for attacks (like the pulling back of a bow string). Yes, it’s

not the beautiful standard straight postured position, but this position is

like a person holding a bow but yet to pull back the string to fire it. But

again, in saying that, without the standard position, one cannot maximize this

more practical position.

Secondly, allow me to explain kata (the shoulders) from this advanced perspective. I’ll just give one example today.

Of course, in the majority of tsukiwaza the

shoulder is kept down and relaxed. This is utterly essential for speed and

connection to the torso, most obviously to connect and harmoniously interact

with the latissimus-dorsi muscles.

However, in real fighting it is often very

important to raise the shoulders and/or lower the head in relation to the

shoulders as we make our tsuki. In this way we gain maximum coverage from the

opponents blows in that moment.

Again, the reference point of standard

kihon is essential, but one must also practice ‘practical variation from this

point’. I was taught that yama-zuki—with both closed fists (Bassai Dai and

Wankan) and with open hands (Roshu, Hachimon, Kakuyoku Sandan, Senka etcetera)

is, amongst things, representative of this application.

To conclude, I believe (actually, I know)

that when we practice karate techniques in more natural and practical way the

standard kihon, kata and yakusoku kumite gain even greater value/importance in

one’s training regime. However, if people merely stick to these aspects, one’s

karate becomes limited to the context of karate; that is, Dojo Kumite and

Karate competitions. While this is fine, it is not the full art of karate nor

fulfills its original purpose: of being Bujutsu.

The wonderful thing here is that, with

strong standard karate and conscientious effort, the springboard for developing

bujutsu karate is already there. It’s just a matter of further refining these

standard skills and, most importantly, expanding on this by training the

variations from these respective baselines. This point has been a high priority

of my karate thanks to the guidance of wonderful seniors: both here in Japan and abroad.

|

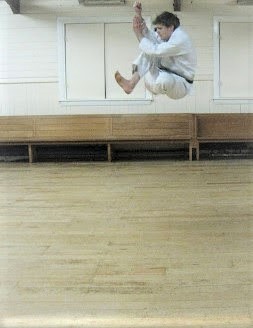

| Ura-mawashi-geri. Kamakura, 2002. |

© André Bertel. Oita City, Japan (2021).

Two days ago my HP laptop suddenly just died and several new projects were lost which, of course, was very disappointing.

What’s most disturbing is that I bought the device in Nevada, USA, in 2019. So it’s pretty new! Moreover, nothing happened, it just died out of the blue. No signs, nothing. I tried all of the checks and tricks, and finally took it to professionals. The result is that ‘it suddenly and randomly died’.

I will say this now. I will NEVER BUY AN HP (Hewlett-Packard)

DEVICE AGAIN. Furthermore, I have had it with Windows. I’m switching fully to Apple now which, until this saga occurred, I would have never dreamed of.

Anyway, this post is giving the birdie to Windows and Hewlett-Packard.

Returning to karate… This situation has delayed some ongoing projects and completely deleted others. The beauty of this is that, regardless of articles, photo, and film, all of this is in our minds and bodies. Therefore as a karateka I can reproduce everything (irrespective of tech). The downer is that I need re-do things. Actually, I was about to release a new video, and that was lost. So very disappointing.

So, from now, I want to purchase and learn how use a Macintosh, which (based on all the crap Windows has given me), will result in superior projects.

I want to apologize for the delays in my written work and videos now, but hope that you will all be enthused by past channel content; moreover, that it motivates your training and contributes to increased knowledge.

Here is a playlist from my official YouTube channel. Please check it out and make some comments on the videos. What would you like to see/learn?

https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLg60uQh-qeJVC7Sm_AAFLck2gl1uRQlSR

I really believe in turning negatives into positives. Of course that is not always possible when the line is crossed, but until that point it is.

That’s the only control we have.

Consequently, it’s utterly imperative to push forward as far as possible with proactivity, a positive attitude and fortitude.

I want wrap up by saying one thing: 押忍 (Osu).

© André Bertel. Oita City, Japan (2021).

浪返し

なみがえし

|

| Asai Tetsuhiko Sensei executing hidari ashi hidari nami-gaeshi (Tekki Shodan Kata). |

(NAMI-GAESHI)

Nami-gaeshi literally translates ‘wave return’ or probably better described in English as ‘returning wave’. The name is derived from the leg action that resembles an ocean wave rolling out then rolling back onto the shore. Of course, the leg action mirrors this, in then out, which is said to represent ‘a constant state of flux’. Beside training in kihon it is first practiced in 鉄騎初段 (Tekki Shodan); later, the fifth常行 (Joko); 騎馬拳 (Kibaken) and, indeed, other kata.

More important than ‘how this waza looks’ and poetic banter, I

want to emphasize its functionality; that is, ‘nami-gaeshi for optimal

application’. Based on this objective I will need to explain ‘how to do it’.

Now, before I go on, I’d like to stress that what I’m going to describe today

is ‘not the standard/general method’ of executing this waza. In fact, the

majority of instructors will say this is incorrect (if they knew this method).

However, it is literally undetectable, even by the most experienced instructors

here in Japan.

The reason I adamantly recommend the method, I going to describe

today, is threefold: (1) It works better when fighting (especially for

ashi-barai (leg/foot sweeping) and/or nagewaza (throwing), also for leg checks

and stamps; (2) It works better because it uses the joints, ligaments,

tendon and muscles ‘naturally’, also it maximizes ‘gravity-based recovery’,

which makes it more explosive; and (3) By being so natural, it does not

harm the body.

Hopefully, I have

your attention now, and hopefully you can also adopt this superior version of

nami-gaeshi.

To begin with…

Let’s consider ‘the standard nami gaeshi’ movement. Basically, from kiba-dachi you swing each leg

inwards and upwards with knee fixed. The leg swings up and becomes parallel

with the fixed knee to ‘form an attractive straight line (from the knee, shin,

and ankle)’. In Shotokan we also ensure that the leg is ‘in front’ as opposed

to being under the stance.

So, what

are the problems with this? Firstly, connecting points 1 and 2 above, (to varying degrees, but

inevitably) it twists the knee; that is, it somewhat uses the knee like a ball

and socket joint as opposed to being natural (needless to say, while the knee

has this capacity). In any case, unless you are genetically very fortunate,

this will be contorting your knee joint.

Accordingly,

the more natural (safe) and powerful method is to use the knee in the way

it’s designed: as a hinge joint. Also, to full engage the hips (I will

expand on this at the end of this article – beyond the basic movement). In this

way one can apply far more power and not contort the sensitive ligaments and

tendons of your knees.

How to do

this? As I have already said, at ‘regular speed’, this is pretty much

indecipherable! So please bear with me on this…

At the start of your action simultaneous push the hip of nami-gaeshi leg forward and rotate the heel of the leg towards the front. When you swing the leg up in this manner, it does not twist but remains in-line (a perfect hinge joint) action. Just to recapitulate, this means that you can sweep and/or impact, or evade, more speedily. Furthermore, by intentionally off-balancing yourself, you can ‘rapidly’ return to kiba-dachi, by maximizing the basic rules of juryoku (gravity). There is another bonus here as well. The ‘hinge joint/natural pushing forward of the hip and rotation of the feel to the front’ also requires 'recovery’—to return to a proper kiba-dachi—which, also contributes to the counter action. Bonus: This is superior if the waza is applied as a fumikomi or leg check. Obviously, if using in reality the positioning is not so set; nevertheless, the practice from kiba-dachi makes it far easier to apply in a natural manner: especially when using the stance as a transitional point in the process of tai-sabaki.

As I

mentioned earlier, there is another element to the hip action. Once this method

is sufficiently refined you can add to the aforementioned hip movement by also

slightly scooping the nami-gaeshi legs hip. This further contributes to power

and effectiveness, and also the counteraction. This perfectly aligns with points

made on my ‘Kinetic Chain’ and ‘Impact Power’ articles. In this regard, “…one

can think of the hip and knee functioning as a single unit” flowing in and out

like the action of a whip: again, the all-important ‘wave action’. Another good

example, for the pushing and twisting actions, is that of baseball pitcher

throwing a spin ball. Suddenly, we can see Asai Sensei’s “…Muchiken (Whip-fist)

expressed in leg/foot techniques”. This is very important to understand and

perfect, especially as we age!

I want emphasize

here that this ‘Asai style’ method of nami-gaeshi was proven firsthand to me as

being ‘more easily applicable and highly effective’ not only when I used to

compete, but also when I worked in security. Rather than being a technique with

a highly specified/limited range of use (and somewhat questionable reliability,

insofar as power is concerned) this method makes nami-gaeshi a highly robust and

broadly applicable karate-waza.

Finally, I hope that this article

contributes not only to ‘more efficient nami-gaeshi’ but also healthier knee

joints, tendons and ligaments. I believed Karate should be—if one

wishes—‘Lifetime Budo’. As such, “…outdated movements, which damage the body, must

be improved/refined, so they are no longer detrimental for our health”. This

has even greater value if ‘form is not compromised’; moreover, the respective

techniques are made more effective. What I have presented here today, with

nami-gaeshi, is an example of fulfilling these points. Best of health and

training, Osu! André

|

| "Biomechanically sound movement and optimal explosiveness are one; therefore, we not only protecting our bodies, when we move naturally, but also maximize our efficiency in application." (T. Asai) |

© André Bertel. Oita City, Japan (2021).

When discussing the science behind

the percussive blows of Shotokan Karate there are, of course, numerous ways to

do so. However, irrespective of the angle we take, we must take heed the underpinning ‘base

science’. Today I thought I’d spell this out in the simplest terms, which can

be directly used in training—by anyone—to increase impact power. I’ll do this, in this post, by outlining three key points.

Firstly, FORCE (the IMPULSE—MOMENTUM

RELATIONSHIP) and the factors involved (velocity, mass, and structure).

Secondly, it is also necessary to expand this by elucidating ‘The KINETIC CHAIN.

Thirdly, I’ll conclude with BODY STRUCTURE’ to essentially support the kinetic chain. Taken as a whole, all three of

these aspects collectively underpin the level of Kinetic Energy that can be

transferred into a target.

‘The

Impulse—Momentum Relationship’ is derived from Newton’s Second Law of Motion. Keeping this

nice and simple, the concept refers to the physics of mass and velocity in

karate ‘tsuki’, ‘keri’ and ‘uchi’ (and indeed ‘ukewaza’ as well, when applied

as a percussive attack). Basically, this is the combination of speed and

strength ‘behind your respective waza’. In sum, Newton’s Second Law of Motion

can be simplified into ‘FORCE = MASS x ACCELERATION’. The elements in this

equation can be further and better expressed as KINETIC ENERGY (KE). Of course,

kinetic energy is the energy an object has due to motion; thus, in karate this

is a fist, open hand, elbow, knee, foot, and so on. This is the formula that is

referred to as ‘the Impulse—Momentum Relationship’, which allows one “…to

acquire much more specific information about ‘the underpinnings’ of power

generation”. Firstly, it establishes that the velocity (speed) has more of an influence

on the energy of karate waza than mass (weight). Again, in the most laymen’s

terms, this is because velocity is squared. This is precisely why science shows

that it is more important to throw a rapid technique than a heavy one. Of

course, however, it is obvious that both are still important. For example, a

very fast kizami-zuki with no weight behind it would obviously have very

limited impact power.

Overall, “…the

most destructive karate-waza will both maximize the mass (weight) behind them

and, more importantly, maximize velocity (speed)”. On top of this, engaging

‘the entire body’ in an optimally coordinated way’—optimizing the Kinetic

Chain—will further increase the destructiveness of one’s percussive blows.

Whilst

understanding the ‘Impulse—Momentum Relationship’ provides “…a mathematical

basis for understanding the forces that make up the percussive blows of

karate”, it doesn’t fully really explain what goes into these respective

forces.

‘The

Kinetic Chain’: Firstly,

as previous as I previously stated, “one must attempt to maximize the mass

behind the respective waza being applied”. This is achieved by engaging the

entire body. To comprehend what this actually means, one has to understand ‘the

Kinetic Chain’. Once again, in basic terms, this is the linking of the muscles

throughout the body to optimally accomplish a single movement/action. The most

powerful waza will activate multiple muscle groups; moreover, link these

different muscle groups together in one fluid motion. This is something I’ve

written and taught a lot about—not only pertaining to muscles but also to the joints—which,

I learned via Asai Tetsuhiko Sensei’s teachings. In fact, for those who follow

Asai Sensei’s karate, this is more important; however, today I am writing more

generally and ‘muscle focused. If you are further interested, here is an article

homing in on using the joints for ‘snap’—actually a more advanced ‘perspective’

than today—here’s a direct link: André

Bertel's Karate-Do: The Kinetic Chain (andrebertel.blogspot.com)

Overall, the

better you can “…link these muscles together (and especially, the joints) in

one seamless and correctly ordered motion”, the more destructive one’s

respective waza will be.

‘Body

Structure’: Consider

facing a pitcher with both a solid bat and a broken one. In the case of solid

bat, it can transfer a large amount of force—as a solid piece of wood—into the

incoming ball. Conversely, the broken bat, upon striking the ball, it will

absorb a significant amount of force; thus, reducing the power of the impact to

propel the ball.

With this

example in mind, it is easy to determine that poor form and structure in uke,

tsuki, keri and uchi will have the same results; that is, “your body will

absorb back a percentage of the targets power. Therefore, we must train to reduce

metaphoric breaking points in our body structure. In this regard, correct joint

alignment will significantly (and simultaneously) increase the efficacy of

karate-waza and help to protect our joints.

Lastly, I want emphasize the need for

karateka to apply these in points in their physical training. In particular,

from this basic understanding, one can test and refine techniques so that their

maximum potential can be realized. Overall, while this article has been very

generic, simple, and probably not that well written, I believe the content

presented today is very worth giving attention to: in order to evaluate and

improve percussive/impact power.

© André Bertel. Oita City, Japan (2021).

I was recently asked to talk about why there are jumps in the Shotokan kata, which pre-Shotokan just weren't there. Now before I answer that question, I want to emphasize that my answer to this question is second-hand; that is, and obviously, I can only reply to this question by what I’ve been told from some of my seniors here in Japan. That being said, I think the answer is logical: they are good for training and better for applying this these kata movements. In sum, pragmatic and, I have to say, 'cool' as well. Therefore, I will share this with you today.

As you will

know, older versions of the kata, for the most part, do not have many of these jumps. To make

the list, not too exhaustive, I will focus on the standard Shotokan Kata featuring

tobi-waza (excluding the majority of low jumps and Nidan-keriwaza). These kata are Heian Godan

(Pinan Godan), Enpi (Wanshu), Kanku Sho (Kosukun Sho/Kushanku Sho), Unsu

(Unshu) and Meikyo (Rohai).

In most

cases, up until Shotokan, the jumps in these kata were 'grounded turns'; nevertheless, the actual applications were the same.

So, who and

why were the jumps added???

Apparently,

Funakoshi Yoshitaka (Gigo) Sensei, overseen by Funakoshi Gichin Sensei, decided

to increase the athleticism of the turns. However, this extra requirement of muscular

spring was “…to strengthen the lower body (for the application of the

respective waza being applied)”. Put another way, “when the kata is practiced

by oneself, there is no training partner to throw”; thus, one throws

themselves. You see, ‘the jump trains the main muscles you actually use to

throw someone in addition to the turns (which tell us the direction of ‘push

and pull’/leverage in order to make that particular throw).

|

| Meikyo Kata: The SANKAKU-TOBI. |

Nevertheless, it doesn’t end there. There are of course exceptions. For example, the Sankaku-tobi of Meikyo is literally a takedown utilizing the combination of tenshin (rotation) and juryoku (gravity) in combination with ‘migi hiji sasho ate’.

The second jump in Kanku Sho is a ‘mikazuki-geri/migi sasho-ate’ followed immediately by ‘a level and sharp falling twisting jump’. Within this is, of course, is the ushiro-kekomi completed by a duck’. In this case, the ‘jumping action’ is “…to enable immediate multi-directional keriwaza”. Indeed, Unsu has a high jump with the same meaning of Kanku-Sho; however, it also can be applied when one’s leg is grabbed (you jump and kick the opponent with the grounded foot—mikazuki-geri, free the other leg, then you kick them again—with ushiro-kekomi). Alteratively, it is also a template for all five versions of Kani-basami.

|

| Here I'm using Kani-Basami in Jiyu Kumite during an exam. |

Just to confirm (and going in reverse order): the jump in Enpi and the first jump in Kanku-Sho are both ‘Kata-Guruma’. Lastly, the jump in Heian Godan is ‘Seoi-Nage’.

I need to

go, ever so slightly, off topic here. As I have written about so much in the

past, Asai Tetsuhiko Sensei stressed ‘three types/styles/modes’ of karate:

“standing, grounded and jumping”. He topped these off with his one of his

‘tokuiwaza’—TENSHIN (rotating/spinning). When you combine these aspects, and

think about the aforementioned applications, I think that one can have a

foundational understanding and unpredictability of Asai Karate.

As already mentioned, the strength benefits from jumping cannot be underestimated. Plyometric exercises and jumping techniques not found in the kata irrefutably have their benefits: especially pertaining to ‘increasing explosiveness’. In addition to this, “…accuracy determined by body control are also useful skills for budoka”; accordingly, the physical education gained from various jumps is significant.

I’d like to wrap up by saying what I always say about kata and their respective oyo (application). Yes, the solo practice of the kata is important as we can really develop our form; furthermore, we can do techniques at full-speed/with maximum capacity without needing to ‘put the breaks on’ (which is obviously essential to avoid injuring training partners). Nonetheless, solo practice is not enough on its own. Of course, it is impossible to make the techniques in the kata ‘functional’ without extensive partner training of the respective kata movements. This point cannot be overstated nor overlooked! Otherwise, kata is nothing more than movement resembling karate, but with no real meaning. Kata in such a shallow way might function as a method of physical fitness/strengthening, however, if that is the case, I believe it would be much more productive spending more time doing resistance training. This in itself is proof that kata includes this aspect, but must also include maximum applicability in conjunction with optimal form and visa-versa.

|

| 青柳 (SEIRYU) Kata |

Some karate instructors love to cite Hick’s Law. I will address this today firstly (and briefly) by explaining it; secondly, by stating its merits; and thirdly and finally, by pointing out its value but, also, its incompleteness (but still pragmatic importance). Before I do those three things, I want to state here that unlike some, I’m not ‘really into’ Hick’s Law, nor am I against it. In my opinion, it is ‘a very simple theory that has great value for the masses’; thereby, irrespective of one’s ‘level of liking’, it is an extremely useful lense. I believe that this is the best way for Budoka to understand Hick’s Law (whilst keeping it in context).

So, what

is it? Hick’s Law

(also sometimes referred to as the Hick-Hyman Law) was established by American

psychologists Edmund Hick and Ray Hyman. Hicks Law is the basic idea that

proposes “…the more choices an individual is given, the decision process will

take a longer time for the individual”. Put another way, increasing the number

of choices naturally increases the decision time logarithmically. OK, so on to

its merits…

The theoretical

value of Hick’s Law:

There is no question that this theory has value for Karateka (in fact all self-defense/fighting

arts), especially in the context of responding to a sudden and violent attack

(which is the whole point). Over the years I have seen so many different

instructors demonstrate and teach—as everyone who reads this will have—'vast arrays

of responses to various attacks and self-defense scenario’s’. As you know,

there are ‘so many techniques, movements and tactic’s’. Obviously, Hicks Law

would say that this is a disadvantage which, for the most part, is undeniably

true. But here’s the thing: this it is only a disadvantage ‘for most people’,

not everyone, and this is where we have a slight problem! Of course, any law is not

perfect.

Hick’s Law

covers ALMOST EVERYONE: A weakness in this theory is that it only accounts for beginners,

intermediate, and ‘probably a significant percentage of practitioners with

higher levels of skill’. Nonetheless, it fails to account for the real elite-level

budoka.

I need to

expand on this, as it seems some people get confused about ‘what an elite level

of skill is’ in Budo Karate. Firstly, allow me to confirm ‘what it isn’t’,

which greatly establishes the void between budo and sports/recreational/demonstration

karate. An elite level in budo karate is “…not only being able to do precise

and sharp movement’s”. No, this is just movement! This is a performance. Elite

skill is where someone can “…use precise karate movements to rapidly and effectively

respond to an attacker (or attackers) who is/are both uncooperative and seriously

attempting to cause physical harm”. This is ‘movement with substance’; that is:

“kihon, kata, and kumite skill with maximum effect in the real world”.

Taken as a whole, budo karateka—at this level—go well outside of the boundaries of Hick’s Law ‘as they can, and will, spontaneously respond with whatever is effective’. At that point, they can pretty much respond with anything without thought.

So, what

can we learn from Hick’s Law? Well, in my opinion, we can establish that, the first and

on-going technical aim of karateka must be to develop a handful of techniques/skills

to a very high level. That is, to develop a few highly volatile and reliable

waza ‘specifically optimal for the individual’s physique, strength, health, and

so on’.

Unambiguously,

this is ‘the best that most practitioners will ever be able to do’, and Hick’s

Law helps us to see this fact, which is great! Thank you, Hick’s Law. A cup of realism.

Translating this into real world application… To me, this means that “…instructors

are cheating their students out of effective self-defense if they don’t

prioritize this point in training”. The reality is that most instructors are mostly training others for the grading syllabus, competition success, or some weird self journey of 'feelings'. This is not true karate. True karate is ichigeki-hissatsu. It is not a joke, sport, nor fake show of moves. But, of course, it can be. The question is what people want. The real or the charade? Always keep this in mind if you are seeking TRUE KARATE.

Lastly, I need to add that even for those who transcend

the boundaries of Hick’s Law—or will in the future—they must still go through the

process of training just a few choices/options/waza to the highest level.

I hope this article helped you realistically

see where Hick’s Law sits in relation to Karate and Budo in general. Osu, André

Yesterday I celebrated 40 years of practicing Karate-Do. In this regard, I need to thank so many people for their amazing support. Literally, no one can do this on their own. Here is my self-training, today, on this first day of the Japanese Autumn. I also hope that it is my first day of my ‘second set’ of 40 years. 押忍, André

基本 (KIHON)

1. Heiko-zuki (Shizentai).

2. Jodan

uchi-uke (koten uchi-uke) kara kizami mae-geri (Nekoashi-dachi).

3. Niren

choku-zuki (Kiba-dachi) kara sonoba naname gyaku-zuki (Zenkutsu-dachi),

zenshin gyaku-zuki, koutai gyaku-zuki, sonoba naname gyaku-zuki, zenshin gyaku-zuki,

koutai gyaku-zuki, choku-zuki (Kiba-dachi), mae tobi-konde choku-zuki soshite

ushiro tobi-konde choku-zuki.

4. Gedan-barai

kara chudan oi-zuki (Fundamentals from Heian Shodan kata).

5. Gedan-barai

kara jodan age-uke/chudan soto-uke (Fundamentals from the ‘Jo no kata exercise’).

型

(KATA)

I.

序の型 (Jo no kata)

II.

鉄騎初段 (Tekki Shodan)

III.

鉄騎二段 (Tekki Nidan)

IV.

抜賽大 (Bassai Dai)

V.

旋花 (Senka)

Iriguchi-waza followed by a kansetsu-waza:

a. Gedan-barai

b. Jodan age-uke

c. Chudan soto-uke

Level up practice: — Extension of this training firstly, using the kihon of the ‘Jo no

kata exercise’; secondly, using the Tegumi (手組) or Mutō (無刀)

drills and principles of Tekki; thirdly, the henka-waza (変化技) of Bassai-Dai; and fourthly, adding tenshin (転身) to these elements via Senka.

© André Bertel. Oita City, Japan (2021).