Following up from my last article here is

a technical summary of Kanku Dai Kata. The numbers convey the correct command

count, which is optimally for perfecting ‘kime’ in every waza. This is

especially notable in renzokuwaza (combination techniques) and, in particular,

in the first movement of sequences. All too common, in sports karate, this

action is weak and ineffective. This is because the aim is to artificially make

more rapid actions in order to appear more explosive/dramatic. This type of

movement must be avoided at all costs for those seeking budo karate as it not

only has no meaning, but also provides an obvious gap in one’s defense.

Kata are not ‘for making bad habits’, so each waza must be maximumly effective. Every time the aim is ICHIGEKI-HISSATSU, which is the only way one can seek optimization in every action. While there is a literal meaning in this, more importantly, the relentless chasing of this technical ambition is what drives the budo karateka forward in their development/refinement of technique, physicality, mentality and heart.

Finally I’d like to mention ‘variations

of kata’ between different organizations, dojo (plural) and individuals.

Obviously, this is not only for Kanku Dai, but all kata and karate waza. One

thing you will easily notice is the Kanku Dai of JKA is different from SKIF,

likewise the JKS version is different from both of these groups. I could go on;

however, I think it is fair to say that there are subtle—and sometimes not so

subtle—differences between individuals, clubs, groups etc...

Hey you! Your shuto uke is too

extended!!! That’s wrong! So and so Sensei in Japan said ‘this is correct’.

This type of thing is OK when we are talking about beginners and intermediate

level karateka. At these stages one needs strict guidelines to acquire a line

of reference. But the individual must grow and moderate themselves—to literally

optimize themselves as budoka—from the standardized versions.

I personally respect ALL VARIATIONS as

long as they are pragmatic in application and avoid superfluous actions. As an

instructor, I teach the way I was taught; however, I avoid correcting

variations which are equally effective. In saying that, I will teach my way if

karateka are interested. When this occurs, I recommend that they experiment and

find the best way for themselves. I could never say to someone that Kanazawa

Hirokazu Sensei’s version of any kata is wrong, likewise Yahara Mikio Sensei et

al. I have deep respect for all of these groups and variations, which are

steeped in budo karate.

That is why, in a grading, if one

presents a rendition of a kata—which is different from mine—if it is correct in

the budo sense and of the appropriate level for the respective grade, I cannot

fail them. To do so would be folly; moreover, representative of the commercial

monopoly which, so often, organized karate is.

Rather with our necks tilted, eyes and

minds looking at the ground, we should be LOOKING AT THE SKY. On that note,

here is Kanku Dai generically summarized.

KANKU DAI

REI (Musubi dachi).

YOI (Hachiji dachi)—Ryo te kafukubu mae.

- Ryo

te hitai mae ue (Hachij dachi).

- Ryo

te kafukubu mae (Hachiji dachi).

- Hidari

haiwan Hidari sokumen jodan uke, usho mune mae kamae (Migi kokutsu dachi).

- Migi

haiwan migi sokumen jodan uke, sasho mune mae kamae (Hidari kokutsu

dachi).

- Hidari

tate shuto chudan uke, uken migi koshi (Hachiji dachi).

- Uken

chudan choku zuki, saken Hidari koshi (Hachiji dachi).

- Migi

chudan uchi uke (Hidari hiza kutsu).

- Saken

chudan choku zuki, uken migi koshi (Hachiji dachi).

- Hidari

chudan uchi uke (Migi hiza kutsu).

- Ryo

ken hidari koshi kamae (Okuri bashi kara hidari ashi dachi).

- Migi sokuto yoko geri keage doji ni migi uraken jodan

yokomawashi uchi (Hidari ashi dachi).

- Hidari

shuto chudan uke (Migi kokutsu dachi).

- Migi

shuto chudan uke (Hidari kokutsu dachi).

- Hidari

shuto chudan uke (Migi kokutsu dachi).

- Sasho

chudan osae uke doji ni migi chudan tateshihon nukite (Migi zenkutsu

dachi)—KIAI!

- Hidari

shuto koho gedan barai kara sasho jodan uke soshite migi shuto jodan

sotomawashi uchi (Hidari shokutsu dachi, gyaku hanmi).

- Migi

jodan mae geri keage (Hidari ashi dachi).

- Migi

sokumen jodan uchi uke doji ni hidari sokumen gedan barai (Migi

kokutsu-dachi).

- Sasho

jodan nagashi uke doji ni migi shuto gedan uchikomi (Hidari ashi

zenkutsu).

- Saken

gedan, uken migi koshi (Hidari ashi mae renoji dachi).

- Sasho

jodan uke doji ni migi shuto jodan sotomawashi uchi (Hidari shokutsu

dachi, gyaku hanmi).

- Migi

jodan mae geri keage (Hidari ashi dachi).

- Migi

sokumen jodan uchi uke doji ni hidari sokumen gedan barai (Migi

kokutsu-dachi).

- Sasho

jodan nagashi uke doji ni migi shuto gedan uchikomi (Hidari ashi

zenkutsu).

- Saken

gedan, uken migi koshi (Hidari ashi mae renoji dachi).

- Ryo

ken migi koshi kamae (Migi ashi dachi).

- Hidari sokuto yoko geri keage doji ni hidari uraken

jodan yokomawashi uchi (Migi ashi dachi).

- Sasho

ni migi chudan mae enpi uchi, usho hidari hiji ate (Hidari zenkutsu

dachi).

- Ryo

ken hidari koshi kamae (Hidari sagi ashi dachi).

- Migi sokuto yoko geri keage doji ni migi uraken jodan

yokomawashi uchi (Hidari sagi ashi dachi).

- Usho

ni hidari chudan mae enpi uchi, sasho migi hiji ate (Migi zenkutsu dachi).

- Hidari

shuto chudan uke (Migi kokutsu dachi).

- Migi

shuto chudan uke (Hidari kokutsu dachi).

- Migi

shuto chudan uke (Hidari kokutsu dachi).

- Hidari

shuto chudan uke (Migi kokutsu dachi).

- Hidari

shuto koho gedan barai kara sasho jodan uke soshite migi shuto jodan

sotomawashi uchi (Hidari shokutsu dachi, gyaku hanmi).

- Migi

jodan mae geri keage (Hidari ashi dachi).

- Migi

uraken tatemawashi uchi, saken Hidari koshi (Migi ashi mae kosa dachi).

- Migi

chudan uchi uke (Migi zenkutsu dachi).

- Hidari

chudan gyaku zuki (Migi zenkutsu dachi).

- Uken

chudan maete zuki (Migi zenkutsu dachi).

- Sasho

soede migi jodan ura zuki doji ni migi hiza zuchi (Hidari ashi dachi).

- Ude

tate (Migi ashi zenkutsu).

- Hidari shuto gedan uke, migi shuto mune mae kamae (Migi kokutsu dachi).

|

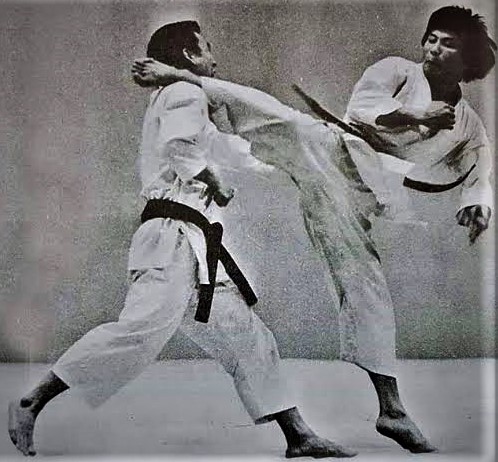

| Kase Taiji Sensei executing movement 44 of Kanku Dai: the extended kokutsu-dachi. |

- Migi

shuto chudan uke (Hidari kokutsu dachi).

- Hidari

chudan uchi uke (Hidari zenkutsu dachi).

- Migi

chudan gyaku zuki (Hidari zenkutsu dachi).

- Migi

chudan uchi uke (Migi zenkutsu dachi).

- Hidari

chudan gyaku zuki (Migi zenkutsu dachi).

- Uken

chudan maete zuki (Migi zenkutsu dachi).

- Ryo

ken hidari koshi kamae (Hidari ashi dachi).

- Migi sokuto yoko geri keage doji ni migi uraken jodan

yokomawashi uchi (Hidari ashi dachi).

- Hidari

shuto chudan uke (Migi kokutsu dachi).

- Sasho

chudan osae uke doji ni migi chudan tateshihon nukite (Migi zenkutsu

dachi).

- Hidari

uraken Hidari sokumen jodan tatemawashi uchi, uken migi koshi (Kiba

dachi).

- Hidari

kentsui chudan yokomawashi uchi (Hidari e yori ashi, Kiba dachi).

- Hidari

sokumen migi chudan mae enpi uchi, sasho migi hiji ate (Kiba dachi).

- Ryo

ken Hidari koshi kamae (Kiba dachi).

- Migi

sokumen gedan barai (Kiba dachi).

- Hidari

zenwan gedan uke doji ni uken furi age (Fumikomi, Kiba dachi).

- Uken

otoshi zuki (Kiba dachi).

- Kaisho

jodan kosa uke (Hachiji dachi).

- (Migi

ashi jiku migi mawari kara Migi zenkutsu dachi).

- Ryoken

mune mae (Migi zenkutsu dachi).

- Nidan

geri kara migi uraken jodan tatemwashi uchi, saken Hidari koshi (Migi

zenkutsu dachi)—KIAI!

|

| Asai Sensei executing the first of the two kicks in Nidan-geri: the 65th count of Kanku Dai. |

NAORE—Migi zenwan migi sokumen sukui kara ryo ken daitai mae (Hachiji dachi).

REI (Musubi dachi).

© André Bertel. Oita City, Japan (2021).