|

| Extension in yoko-geri kekomi is not to 'reach' but to 'go through' the respective target. |

足刀横蹴蹴込 (Sokuto yoko-geri kekomi) more commonly and conveniently just referred to as 'Yoko-kekomi; is one of the five main 蹴技 (kicking techniques) of Shotokan Karate. It is also the first ‘thrust kick’ taught. In competition, in my teens and 20s, I have used this waza and stopped several matches due to the opponent not being able to continue, sadly even hospitalized one. In many tournaments it is not scored as the user has inadequate power or incorrect kihon within their kekomi. I’ve also used this waza for defense, when working in security: although, not as a kime-waza, but rather to break the distance. I wish I could say otherwise, but street fighting is different from any form of competition. Today’s article will highlight the key points to practice and develop a highly effective and reliable yoko-geri kekomi. Beyond this I’ll also provide some other information for clarity and some other related aspects. Overall, I hope you find it worth a read and useful for training and teaching.

BASIC IDOKIHON TRAINING (KIBA-DACHI)

Before beginning I want to say that I could have started by discussing stationary training from Heisoku-dachi etcetera; nevertheless, I decided to instead primarily focus on linework in kiba-dachi; that is, 'moving the center'. In other words, the underlying focus in this article is power generation and optimal impact potential. Later, I'll address yoko-kekomi practiced and used in other forms from this baseline.

1. From

kiba-dachi (hands in the freestyle kamae) with the right hip facing shomen, without

changing height, draw up the left foot and cross it tightly in front of the

right.

2. At this

point raise the knee as high as possible as if performing a mae-geri 90 degrees

away from shomen. It is essential at this point to keep the left sasae-ashi compressed

by remaining bent in contrast with highly raised knee. All of the weight must

be transferred to the left leg. It is important to note here that front and

side pelvic alignment, back, and head/neck posture must all be straight. Again,

the position of a making a proper mae-geri is the best reference point. In sum,

this position must optimize shisei (posture) of the johanshin (upper body) in

perfect harmony with compression of the kahanshin (lower body).

3. At this point keeping the posture—avoiding leaning back, and keeping the compression of the sasae-ashi—open the hips. This occurs until you sokuto is aimed directly at the respective target. In sum, this is the completion of 'chambering/loading the kekomi'.

4. From this

position drive the kicking 'sword foot' in a straight line (imagine the sokuto travelling down a horizontal pipe placed between your chambered position and your target) by straightening the kicking legs

knee and expanding/straightening the sasae-ashi. It is critical to fully use

ground power via the sasae-ashi. This means that energy must not go upwards

but, rather, the hips must driven towards the target. The feeling, when making

a correct kick, and I will quote Tanaka

Masahiko Sensei here, is that “…you should aim to drive your hips

through your opponent”. To achieve this allow the grounded foot to pivot naturally to allow

the hip joint to fully open and permit the knee to optimally function as a

hinge joint. Another key point in the extension and impact stage of yoko-kekomi

is that the hips will tilt, however, the weight of the upper body must go

forwards. Lastly, be sure that the heel is slightly higher than the small toe

side of the foot; furthermore, all the toes of the kicking foot are pulled back

in the josokutei formation (as in mae-geri). Just an additional tip here... Straighten the knee of the kicking leg, but don't hyper extend! Straightening the leg is not concluded by the bones, joints. ligaments, nor tendons... Certainly not a scientific comment here, but I'm trying to make a point. The straightening/extension of the leg is concluded by muscle alignment upon completion. This gives a couple of millimeters, which means the muscles take care of/buffer things, as opposed to the alternative negatives.

5. When withdrawing the kicking leg don’t allow the knee to drop; instead, bring it back on a level plane returning to the aforementioned mae geri position. Note as the posture is recovered that the support leg is also once again compressed. This action not only means one’s balance has been recovered but, also, that the body is coiled again. What’s, more it is natural in the stage by stage process of ‘landing your stance’. Of course, points one to five here are all individual aspects that must be properly executed, however, they must seamlessly flow in one continuous action; thereby, not losing momentum. Put another way, each aspect builds up the total momentum, then recovery. From the beginning of kosa-aiyumibashi, the cross stepping action, one complete the following motions in a continuous 'wave-like' action.

After reforming into a good kiba-dachi (here too, you can imagine a receding wave) one repeats

the process as many times as directed to do in the class (or as ‘set’ or ‘needed’ in self

training). Of course, to practice on the opposite side with the other leg,

simply turns their head and kamae 180 degrees.

6. Needless

to say, equal practice of both sides is essential in general group classes; however,

in self-practice I tend to do around 25% more ‘good repetitions’ of any

technique I find that is weaker on one side.

|

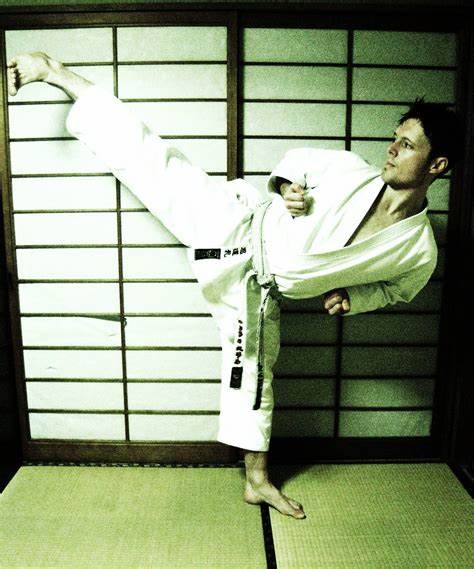

| Asai Sensei: Jodan yoko-geri kekomi |

A FEW KEYS POINTS

B. Take care when launching yoko-geri kekomi from

zenkutsu-dachi and jiyu-dachi. The knee should still be raised like a mae-geri;

that is, the body should not turn over too early. Yes, it is true that this

telegraphs your kick, but more than that, it’s a very weak position.

C. In kumite beware of kiba-dachi! Whether it’s

Yakusoku-Kumite (say Kihon Ippon Kumite or Jiyu Ippon Kumite) or, indeed, Jiyu

Kumite, if your opponent defends your yoko-kekomi. Don’t land in kiba-dachi.

Make sure you control your recovery and landing so that you are in a front

facing tachikata. I can’t count the number of times I’ve seen people have their

kekomi deflected by, soto-uke, then observing land in a passive kiba-dachi. My

point here is that even in Yakusoku Kumite, where you are only throwing one

waza, still “… face them, watch their defense and counter, and mental counter

their counterattack or image your immediate follow up”. This recovery period

and especially ‘how you recover’ largely determines the power and speed in any

follow up waza.

D. When making a kizami yoko-geri kekomi the best waza

combines all of the previous points; however, the situation differs for optimal

effect. The best kizami yoko-kekomi is when the opponent charges in. In this

case, a collision impact can be achieved. Still, if one is not significantly

bigger and/or stronger than one’s opponent, this kick will require good kihon

to be very effective. Therefore, please practice and keep in mind, all of the

aforementioned fundamentals; thereby, making them automatic: irrespective of

‘the type of yoko-kekomi’ you are practicing or applying.

What about gedan kekomi? Lastly, you will have probably noticed that I concentrated on the chudan kick, as opposed to gedan (i.e. – migi sokuto gedan-kekomi in the two Bassai kata, and so forth). This was intentional as they have unique subtleties which, sharing most technical characteristics, also differ in some aspects.

|

| Osaka Sensei making me 'show the exact way'. |

What about that big jodan kekomi? Well, I think this is

great physical training and, rather than height, is great for the

depth/penetration of one’s leg techniques. That is, not reaching, but as Tanaka

Sensei stressed ‘going through the target’. When teaching it greatly expresses

this point and, in enbu (demonstrations) it establishes that the demonstrator

can plant their kicks anywhere they decide. In any case, it is a highly visible

display of the Tai No Shinshuku in Karate.

Surely, you can’t forget tobi yoko-kekomi!? Yes, the jumping

side thrust kick is a classic/signature showcase waza but, more importantly,

(as I’ve discussed in the past on this site) jumping techniques—including tobi

keriwaza—are primarily for the strengthening of the body. For example, “…more

important than jumping height is how much, and how tight, can one contract

their body”. The tighter and more closed in a jump, the more explosive

expansion can be made. As a side note and interestingly, with rudimentary

physical prowess, such jumping waza are easier than the grounded kihon

versions. There is a saying that relates to this: “Show an average gymnast the

Unsu jump and they will have a great one almost immediately. But show them an

oi-zuki and it will take them years to do it well”.

Kata shouts out a ‘kekomi message’!! I also needed to

address that I’ve highlighted before, but will again here. Keep in mind that

“…there is no ‘grounded kekomi’ of any sort—in the standard Shotokan kata nor

Asai Sensei’s kata—which does not simultaneously pull the opponent in”. The

reason for this is for optimal penetration, positioning, off balancing, and the

opening of the opponents defense. With decent kihon and base strength, ‘even a not

so physically strong karateka can break an opponents upper ribs, sternum or

leg’ if tsukami-uke or ryosho tsukami-uke is properly applied. It also means

that targeting becomes a far simpler motor skill, which is a critical factor in

real fights.

Of course, no article can compensate for practice and training, an excellent instructor, and high level training partners; nevertheless, this article hopefully helps to clarify 'what a yoko-kekomi, in budo karate, is'. Like all techniques in true karate, the constant strive is to seek each action to finish the opponent: ICHIGEKI HISSATSU. Only in this way, we can maximize our potential by seeking the extremities of human potential.

(c) André Bertel. Oita City, Japan (2022).

No comments:

Post a Comment